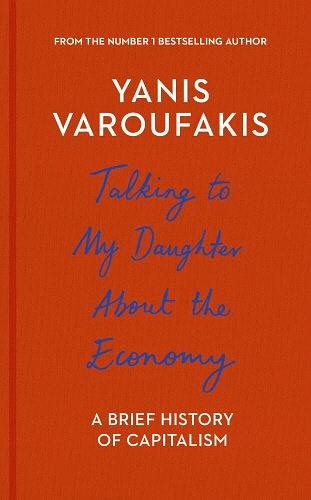

书名:Talking to My Daughter About the EconomyABriefHistoryofCapitalism

作者:YanisVaroufakis

译者:

ISBN:9781847924445

出版社:BodleyHead

出版时间:2017-10-19

格式:epub/mobi/azw3/pdf

页数:224

豆瓣评分: 8.1

书籍简介:

In Talking to My Daughter About the Economy, activist Yanis Varoufakis, Greece’s former finance minister and the author of the international bestseller Adults in the Room, pens a series of letters to his young daughter, educating her about the business, politics, and corruption of world economics. Yanis Varoufakis has appeared before heads of nations, assemblies of experts, and countless students around the world. Now, he faces his most important―and difficult―audience yet. Using clear language and vivid examples, Varoufakis offers a series of letters to his young daughter about the economy: how it operates, where it came from, how it benefits some while impoverishing others. Taking bankers and politicians to task, he explains the historical origins of inequality among and within nations, questions the pervasive notion that everything has its price, and shows why economic instability is a chronic risk. Finally, he discusses the inability of market-driven policies to address the rapidly declining health of the planet his daughter’s generation stands to inherit. Throughout, Varoufakis wears his expertise lightly. He writes as a parent whose aim is to instruct his daughter on the fundamental questions of our age―and through that knowledge, to equip her against the failures and obfuscations of our current system and point the way toward a more democratic alternative.

作者简介:

Let me begin with a confession: I am a Professor of Economics who has never really trained as an economist. While I may have a PhD in Economics, I do not believe I have ever attended more than a few lectures on economics! But let's take things one at a time.

I was born in Athens back in the mists of 1961. Greece was, at the time, struggling to shed the post-civil war veil of totalitarianism. Alas, those hopes were dashed after a brief period of hope and promise. So, by the time I was six, in April of 1967, a military coup d' etat plunged us all into the depths of a hideous neo-Nazi dictatorship. Those bleak days remain with me. They endowed me with a sense of what it means to be both unfree and, at once, convinced that the possibilities for progress and improvement are endless. The dictatorship collapsed when I was at junior high school. This meant that the enthusiasm and political renaissance that followed the junta's collapse coincided with my coming of age. It was to prove a significant factor in the way that I resisted conversion to the ways of anglosaxon cynicism in the years to come.

When the time came to decide on my post-secondary education, around 1976, the prospect of another dictatorship haδ not been erased. Given that students were the first and foremost targets of the military and paramilitary forces, my parents determined that it was too risky for me to stay on in Greece and attend University there. So, off I went, in 1978, to study in Britain. My initial urge was to study physics but I soon came to the conclusion that the lingua franca of political discourse was economics. Thus, I enrolled at the University of Essex to study the dismal science. However, within weeks of lectures I was aghast at the content of my textbooks and the inane musings of my lecturers. Quite clearly economics was only interested in putting together simplistic mathematical models. Worse still, the mathematics utilised were third rate and, consequently, the economic thinking that emanated from it was atrocious. In short shrift I changed my enrolment from the economics to the mathematics school, thinking that if I am going to be reading maths I might as well read proper maths. After graduating from Essex, I moved to the University of Birmingham where I read toward an MSc in Mathematical Statistics. By that stage I was convinced that my escape from economics had been clean and irreversible. How deluded that conviction was! When looking for a thesis topic, I stumbled upon a piece of econometrics (a statistical test of some economic model of industrial disputes) that angered me so much with its methodological sloppiness that I set out to demolish it. That was the trap and I fell right into it. From that moment onwards, a series of anti-economic treatises followed, a Phd in… Economics and, naturally, a career in exclusively Economics Departments, in every one of which I enjoyed debunking that which my colleagues considered to be legitimate 'science'.

Between 1982 and 1988 I taught at the University of Essex, the University of East Anglia and the University of Cambridge. My break from Britain occurred in 1987 on the night of Mrs Thatcher's third election victory. It was too much to bear. Soon I started planning my escape. But where to? Continental Europe was closed to non-native academics, at that time, and Greece awaited with open arms – to enlist me into its conscript army. No, thanks, I thought to myself. Even Thatcherism is preferrable. My break came shortly after when, out of the blue, I was invited to take up a lectureship at the University of Sydney. And so the die was cast. From 1988 to 2000 I lived and worked in Sydney, with short stints at the University of Glasgow (and an even shorter one at the Université Catholique de Louvain). In 2000 a combination of nostalgia and abhorrence of the concervative turn of the land down under (under the government of that awful little man, John Howard) led me to return to Greece

书友短评:

@ Atsu 解释债务如何塑造了资本主义:创业需要启动资金,靠储蓄大多是不足的,就必须借债。封建社会时有偿借贷是为人不齿的犯罪行为,但当举债变成了经济活动的必要环节,上层阶级就回顾性地创造出了一系列道德观来合理化债务的存在。在浮士德这一经典故事中,16世纪的借债人浮士德博士为偿还债务“堕入地狱”自食苦果,而到了19世纪的歌德笔下,浮士德享受了魔鬼的诱惑后又通过行善“redemption”进入天堂,达到皆大欢喜。作者认为,财富不是私人创造的,而是通过资源循环和知识积累创造于社会中,之后才被私有化。投资者的积极性不来自减薪或降息,而是对社会总体经济状况的乐观估计。作者说私有化理论是失败的巫术,民主化劳务市场,货币市场和自然资源的领域决策才是出路。 @ Weissesblatt 经济学(x)左派经济学(√)作者的对话对象是十五岁的女儿,所以没有按照学术标准来写,内容和语言也十分简单。初中生可自学系列。 @ Twist 首先作者的立场很清楚 老老实实经济学讨论真的能脱离政治立场真空存在么 不大可能吧你总要有个自圆其说的出发点 从这个角度上来说这本书写的还是蛮真诚的吧 虽然有些神话类比也是太生硬了 让我们这种人get 一些基本概念和逻辑还是可以的 可以搭配正经教科书学着批判着看看

添加微信公众号:好书天下获取

好书天下

好书天下

评论前必须登录!

注册